Laparoscopic-assisted transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a review of indications, technical considerations, and outcomes

Introduction

Obesity has emerged as a major health care epidemic among all age groups. In the United States the estimated prevalence of obesity exceeds 40% in adults and is nearly 20% in children and adolescents (1). This epidemic carries significant consequences for both individual patients and the health care system. Medical conditions associated with obesity include cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, degenerative joint disease, and cancer, making obesity one of the leading causes of premature and preventable death (2). The annual medical cost of obesity in the United States was recently estimated at $173 billion United States dollars (3).

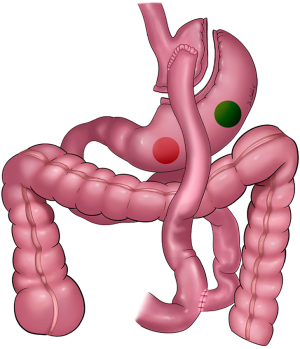

Among those who pursue weight loss treatment, selected individuals may be candidates for bariatric surgery. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is among the most commonly performed bariatric surgical procedures. The American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimates that more than 40,000 RYGB surgeries were performed in the United States in 2020, constituting 21% of all bariatric surgeries (4). The weight loss mechanisms of RYGB are multifactorial, consisting of anatomic restrictive and malabsorptive components as well as alterations in metabolic/hormonal pathways.

An unintended long-term consequence of RYGB is the fact that surgically altered foregut anatomy in the RYGB configuration complicates pancreaticobiliary endoscopy, specifically endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). With the duodenum no longer in continuity with the foregut, the major papilla is not accessible for antegrade access with a duodenoscope via standard peroral means. As a consequence, alternative methods have been devised for endoscopic pancreaticobiliary access following RYGB. A principal alternative is laparoscopic-assisted transgastric ERCP (LATE). This technique consists of laparoscopic access to the excluded gastric remnant to facilitate percutaneous transgastric, transpyloric passage of a duodenoscope to the major papilla.

This review discusses the technique of LATE for endoscopic pancreaticobiliary access following RYGB. Topics will include indications for LATE, surgical and endoscopic techniques including a guide to troubleshooting, discussion of potential adverse events, logistical considerations including staffing and workflow, and finally alternative therapeutic options to LATE and additional factors likely to influence future performance of LATE.

Indications for LATE

Indications for LATE include standard biliary indications for ERCP, similar to those in patients with normal foregut anatomy, including choledocholithiasis, bile leak, bile duct stricture, and jaundice due to extrahepatic bile duct obstruction. The most common indication for ERCP in the post-RYGB patient population is choledocholithiasis. Choledocholithiasis may develop due to one of several pathways including transcystic migration of gallbladder stone(s) in patients with gallbladder in situ, retained previously occult migrated gallbladder stone(s) in patients who have undergone prior cholecystectomy, or formation of de novo primary common duct stone(s) in patients who have undergone prior cholecystectomy. The pathophysiologic milieu favoring gallstone formation may be further enhanced following RYGB, as rapid weight loss is a known potential precipitant of gallstone formation. Gallbladder stones may develop in 36% and gallbladder sludge may develop in an additional 13% of patients at 6 months following gastric bypass, although the majority of these patients remain asymptomatic (5).

The role of prophylactic cholecystectomy in the peri-RYGB period has been a subject of long-standing investigation and debate, the full extent of which is beyond the scope of this manuscript. Some studies have advocated for prophylactic cholecystectomy at the time of RYGB due to the high prevalence of cholelithiasis and associated pathology including chronic cholecystitis (6), and an increased incidence of cholecystectomy including complicated cholecystectomy within 36 months following RYGB compared to the general population (7). Other studies have suggested that the incidence of symptomatic cholelithiasis following RYGB is low (8) even among patients with cholelithiasis diagnosed by screening ultrasound prior to RYGB (9) and have cited an increased risk of major postoperative adverse events following RYGB with concomitant cholecystectomy compared to RYGB alone (10). It is noteworthy for the purposes of this review that the literature on symptomatic biliary disease requiring intervention during follow up for RYGB patients with gallbladder in situ emphasizes the performance of interval cholecystectomy—but does not define as an outcome or report on incidence of interval endoscopic biliary intervention following RYGB as a factor in this debate.

Irrespective, the performance of prophylactic cholecystectomy at the time of RYGB has clearly decreased over time. A large retrospective analysis from a national hospital database reported that the percentage of patients who underwent concomitant cholecystectomy at the time of laparoscopic RYGB declined from 26.3% of surgeries in 2001 to 3.7% of surgeries in 2008. This analysis also cited longer hospital stay and a higher postoperative complication rate in patients who underwent concomitant cholecystectomy (11).

This practice pattern portends an increasingly large proportion of patients with gallbladder in situ at risk for interval symptomatic choledocholithiasis and needing endoscopic biliary intervention such as LATE following RYGB. And indeed, in a large multicenter international cohort of 579 patients who underwent LATE following RYGB, the indication for ERCP was biliary stone in nearly half (47%) of cases (12).

Patients with pancreas-specific indications for ERCP with therapeutic intervention, including pancreatic fistula, pancreatic duct stricture or stone, and selected patients with acute pancreatitis may also be candidates for LATE although represented in smaller numbers in historical cohort analysis (12).

Extreme discretion should be exercised in the decision to pursue LATE for evaluation of asymptomatic biliary duct dilation without laboratory evidence of cholestasis, abdominal or suspected biliary pain without liver biochemical test abnormalities or imaging evidence of biliary duct dilation, or suspected sphincter dysfunction. ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy is largely now restricted to carefully selected patients meeting criteria for high suspicion of sphincter stenosis. And similar to patients with intact foregut anatomy, clinical symptomatic response rates to sphincterotomy via LATE following RYGB are modest when performed for sphincter disorders (13).

Patients with choledocholithiasis and superimposed ascending cholangitis can be successfully treated via LATE. However, for patients with biliary sepsis and acute or impending clinical decompensation, time to mobilization of services and biliary access may be relatively disadvantageous if more expedient temporizing methods of intervention such as percutaneous biliary drainage are readily available. This will be additionally discussed in subsequent sections.

Surgical and endoscopic technique

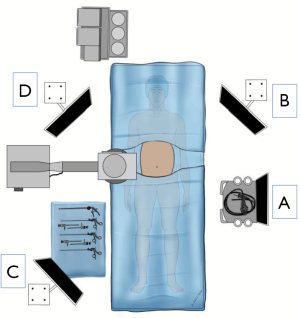

The patient is placed in a supine position with the left arm tucked; a foley catheter is typically not necessary. A footboard is placed, facilitating placing the patient in the reverse Trendelenburg position. Operating room ergonomics and equipment placement are key to facilitating an efficient combined laparoscopic-endoscopic procedure. Placement of the laparoscopic monitors such that the endoscopic and fluoroscopic images can also be easily viewed is important (Figure 1). Considerations should also be made for c-arm positioning and clearance of video monitors. Picture-in-picture capability or monitors capable of simultaneously displaying inputs from multiple video sources can help reduce the number of monitors needed for the procedure.

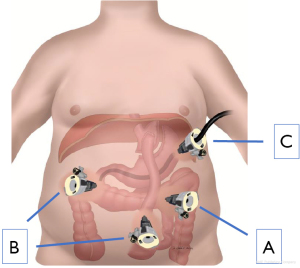

Pneumoperitoneum is established and laparoscopic trocars are placed via standard laparoscopic surgical technique for a foregut procedure (Figure 2). The patient is placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position, displacing the viscera caudally. Adhesiolysis is performed as necessary. Preoperative imaging can help identify the location of the remnant stomach and anticipated complexity of remnant stomach access, but is not necessary depending on the experience of the surgeon. Review of the original gastric bypass operative report is beneficial in terms of location of the Roux limb (antecolic vs. retrocolic). Precise identification of anatomic structures is critical; if at all possible, the Roux limb and gastric pouch should be identified and typical locations for internal herniation quickly visualized depending on clinical suspicion. The surgeon must weigh the extent of these evaluations given the patient’s clinical presentation and radiographic workup. This is especially critical if the etiology of presenting symptoms is uncertain or atypical.

The gastric remnant is usually readily visualized in the left upper abdomen. The anatomic relationship between the remnant stomach and the left costal margin is important to characterize. This relationship will help determine the trajectory of remnant stomach luminal access for LATE and also the means by which the gastrotomy is addressed after the procedure. Once the gastric remnant is identified an access site is identified along the anterior wall of the body of the remnant stomach. It is quite important to place this access site toward the proximal stomach and away from the antrum (Figure 3). This should be balanced by avoiding placing the gastrotomy too high making it difficult to gain access for LATE. Once the site is identified, two seromuscular stay sutures of 2-0 Vicryl are placed on either side of the intended gastrotomy site and brought through the anterior abdominal wall using a suture passer. The externalized sutures are tagged with hemostats. Electrosurgical current or ultrasonic shears are used to create a gastrotomy. It is imperative that luminal access has been confirmed; a generous enough gastrotomy should be created to allow for a 15 mm laparoscopic port. The 15 mm trocar is advanced through the gastrotomy taking great care not to injure the back wall of the stomach. The two previously externalized 2-0 Vicryl sutures can be brought through the external hub of the 15 mm port and clamped securely in place.

To facilitate the endoscopic portion of the procedure, an extremity drape can be placed over the entire operative field, leaving the 15 mm port available through the small opening in the drape. Since duodenoscopes are not stored in sterile fashion after reprocessing and endoscopy is not a sterile procedure, this additional draping ensures sterility of the operative field. The patient is taken out of reverse Trendelenburg position. At the proceduralists’ discretion, laparoscopic insufflation and visualization can be maintained until endoscopic luminal access has been achieved. Typically, once the endoscopic portion of the operation has started, laparoscopic insufflation and visualized are stopped.

A duodenoscope is advanced through the 15 mm trocar and navigates across the pylorus to the duodenum. Once the major papilla is identified and with availability of a C-arm or portable fluoroscopy unit, selective ductal cannulation can be established. Standard ERCP therapeutic techniques can then be performed as dictated by cholangiographic (and/or pancreatographic) findings, including sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and stent placement as indicated.

If the need for repeat future endoscopic access to the papilla is anticipated, for instance for repeat stone therapy in the case of incomplete extraction or for stent manipulation, an externally removal gastrostomy tube can be placed at the gastrostomy site. Should this be required, a laparoscopic gastropexy should be performed using the existing stay sutures and usually two additional sutures. Once a mature fistula has formed, typically a minimum of 4–6 weeks following gastrostomy creation, the gastrostomy tube can be removed, and balloon dilation of the gastrostomy tract can be performed to permit percutaneous introduction of the duodenoscope directly into the gastric remnant for papillary access. If the need for additional endoscopic access is again anticipated, a gastrostomy tube can be replaced; if not, the gastrostomy tract can be left decannulated for gradual spontaneous closure.

Pitfalls, troubleshooting, and limitations

Analysis of learning curves for LATE has demonstrated that competency and optimized outcomes can be achieved with a relatively small volume of cases at both the institutional and individual practitioner levels (14). Nonetheless, the laparoscopic surgery and interventional endoscopy teams who embark on LATE need to be prepared for common pitfalls and possess the ability to engage in creative troubleshooting. In cases involving multiple prior surgical revisions/reinterventions, postoperative anatomy may not always be as anticipated even with close review of high quality preoperative cross-sectional imaging. In some cases the gastric remnant may have been surgically resected and there is no option for gastrostomy. Creation of a jejunotomy may be an option for retrograde duodenoscope access to the papilla in this scenario.

A common novice mistake is placement of a gastric trocar too small to permit duodenoscope passage. The outer diameter of widely used commercially available duodenoscopes is 13.5 mm (TJF-Q190V duodenoscope, Olympus) to 13.6 mm (ED34-i10T2, Pentax Medical) at the distal end. We use a 15 mm diameter trocar to allow easy passage and maneuverability of the duodenoscope.

Once within the stomach, duodenoscopic identification of the pylorus and intubation of the duodenum can be surprisingly challenging at times, especially given that the duodenoscope has side-viewing but not forward-viewing capability. Gastric insufflation to permit distention and optimal visibility can be hindered by pneumoperitoneum. Conversely, endoscopic insufflation of air into the duodenal lumen can distend the small bowel making subsequent laparoscopic visualization difficult. Carbon dioxide endoscopic insufflation is preferred. If the tip of the trocar is angled away from the pylorus, then the endoscopic direction of travel will be towards the gastric fundus. Once identified, this can be remedied by external manipulation of the trocar and redirection of the trocar tip towards the pylorus. A far more challenging problem can be encountered if the gastrotomy is too close to the pylorus rendering the geometry unfavorable to permit angulation and navigation of a large, stiff duodenoscope across the pylorus and around the duodenal sweep. It is therefore critical that the gastrotomy is created on the body of the remnant stomach rather than the gastric antrum (Figures 2,3).

In some cases, for instance in the presence of a periampullary duodenal diverticulum, the major papilla may not be identifiable to permit endoscopic pancreatobiliary access. And even in instances of normal duodenal and papillary anatomy and in the hands of a skilled and experienced endoscopist, selective bile duct cannulation may be unsuccessful in a small percentage of cases. If laparoscopic common bile duct or transcystic access can be established in an instance of failed endoscopic cannulation, antegrade transpapillary placement of a wire can be attempted to permit endoscopic visualization and rendezvous.

Considerations for repeat endoscopic access following LATE carry major limitations with respect to timing. As previously mentioned, if the need for endoscopic re-access to the papilla is anticipated then an externally removable gastrostomy tube can be placed following completion of ERCP. However, this permits elective endoscopic access without laparoscopy only once the percutaneous gastrostomy tract has matured. If more urgent endoscopic re-access is needed, as for example to treat delayed post-sphincterotomy hemorrhage within days of an ERCP or cholangitis due to early biliary stent occlusion and dysfunction, then repeat laparoscopic access to the gastric remnant will need to be established.

Outcomes

Small case series reporting feasibility and high technical success rates of LATE were reported more than a decade ago (15,16). Meta-analysis of accumulated data consisting of 256 patients from 17 case series reported an overall technical success rate of 95% (17).

The largest retrospective study of LATE was reported in 2018 and included an international multicenter cohort of 579 patients. The overwhelming majority of patients (more than 90%) underwent ERCP for a biliary indication, most typically biliary sphincterotomy (96%) followed by stone extraction (44%). Overall technical success was achieved in 98% of cases including a 98% selective ductal cannulation rate. Median procedure time was 152 minutes with a median ERCP time of 40 minutes (12). Performance of LATE need not be confined to academic referral centers, and high rates of technical and clinical success appear reproducible in community hospital settings (18) when laparoscopy and advanced endoscopy expertise are available. Up to 5% of patients undergoing LATE may require conversion to open laparotomy in order to access the gastric remnant (12,18).

Adverse events

Post-operative infection is the most common adverse event. Laparoscopy or trocar-associated perforation should be a rare occurrence. ERCP-related adverse events, including post-sphincterotomy hemorrhage and pancreatitis, appear to be within the standard range seen in patients with normal foregut anatomy who undergo ERCP (12,18).

There are no reported data regarding the impact of RYGB anatomy on endoscopic practice to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) among patients undergoing LATE. A common and often critical strategy to prevent PEP in individuals deemed at high risk for PEP is placement of a prophylactic pancreatic duct stent, in order to preserve pancreatic drainage caused by either edema or trauma to the pancreatic sphincter following instrumentation of the papilla. The needed duration of stent indwell for this purpose is probably only a few days, and the duration of stent indwell should not exceed a few weeks in order to avoid iatrogenic stent-induced pancreatic duct injury. In cases when the stent does not dislodge and pass from the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously, endoscopic removal is typically a simple outpatient procedure in a patient with normal foregut anatomy. However, need for repeat endoscopy to extract a pancreatic stent following LATE may require either repeat surgical access to the gastric remnant or placement of an externally removal gastrostomy tube and delay until maturation of a mature gastrocutaneous fistula to permit dilation and percutaneous scope passage. In the latter scenario, this delay may exceed the intended or ideal duration of stent indwell. In theory, then, barriers to early endoscopic re-access may diminish endoscopist enthusiasm for prophylactic pancreatic stent placement.

Staffing, workflow, and logistical considerations

Given the need for standard surgical equipment and a sterile surgical field, LATE is performed in an operating room setting. Unless in an operating room which also serves dual function as an endoscopy suite and is formatted and stocked for this purpose, necessary endoscopy equipment and accessories can be brought to the operating room on a portable travel endoscopy cart.

Physicians who have dual training in both laparoscopic surgical and ERCP skills are a rarity. In most instances, therefore, performance of LATE requires participation of both a surgeon and an interventional endoscopist. In busy clinical practice this often requires advance planning and careful coordination of physician schedules, therefore LATE may be challenging to arrange in non-elective or urgent/emergent scenarios.

Alternatives to laparoscopy-assisted ERCP

Per oral access to the papilla with a duodenoscope following RYGB is hampered not only by the length of the roux limb but often the angulation of the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis and the difficulty in achieving deeper intubation with one-to-one motion with the scope tip in a highly angulated or even retroflexed orientation. Retrograde access to the papilla may be achieved with a balloon-assisted enteroscope (19) in the hands of a skilled and committed endoscopist, and this offers a potential minimally invasive, natural orifice alternative to LATE. However, balloon assisted enteroscopes may not be available in all facilities which perform ERCP, particularly lower-volume or community-based facilities. Moreover, the lack of a side-viewing component or elevator mechanism, both critical functional features of a duodenoscope, can make visualization of the papilla and ductal cannulation, respectively, challenging via this approach. In the previously described multicenter cohort, 19% of patients who underwent LATE had undergone prior failed attempt at enteroscopy ERCP (12). And a recent multicenter Japanese study of patient who underwent balloon enteroscope-assisted ERCP for removal of common bile duct stones following RYGB reported an 83.7% technical success rate and and 78.1% complete stone clearance rate (20)—impressive results on the one hand, but lower success rates than would be acceptable for patients with normal foregut anatomy and still leaving approximately one fifth of patients requiring an alternative such as LATE.

An alternative endoscopic option is access to the excluded gastric remnant via a gastrogastric fistula of either spontaneous or intentional origin. In an approach known as endoscopic ultrasound directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE), an echoendoscope positioned either within the gastric pouch or jejunum is used to visualize the excluded gastric remnant. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transluminal access to the excluded gastric remnant is achieved, typically with an electrocautery enhanced catheter, followed by placement of a 15 or 20 mm diameter, self-expanding lumen apposing metal stent preloaded on the catheter. Endoscopic transgastric or transjejunal access to the gastric remnant and ultimately duodenum can then be achieved with the duodenoscope, typically following an interval of between several days to up to several weeks to allow expansion of the stent to its full luminal diameter before attempting ERCP. If urgent access to the papilla is needed and cannot be delayed, single-session EDGE has been reported, although this risks migration of the stent (21). Following completion of the ERCP intervention(s), the lumen apposing stent may be left for further indwell if there is potential need for endoscopic re-access to the papilla then removed electively at a later date.

EDGE has been reported with high rates of technical and clinical success (22,23). A potential disadvantage is the multistage nature with need for up to three separate endoscopic procedure sessions (I. stent placement and fistula creation, II. ERCP, III. stent removal). There is also the potential for weight regain if the gastrogastric fistula persists following stent removal (24). However studies have suggested high rates of spontaneous fistula closure following stent removal and the remaining persistent fistulae are typically amenable to endoscopic closure.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and biliary drainage remain an important option for therapeutic biliary intervention in patients with altered foregut anatomy. Skilled interventional radiologists are able to offer a full range of biliary interventions beyond transhepatic drain placement including stent placement and, in some centers, percutaneous cholangioscopy and lithotripsy for stone management. Particularly in a patient with ascending cholangitis, biliary sepsis, and impending or active clinical decompensation, a readily accessible percutaneous intervention may be a faster and therefore prudent initial approach compared to LATE.

Laparoscopic transcystic common duct exploration remains an option for stone management when this expertise is available. This surgical approach may be particularly appropriate in patients with an indication for cholecystectomy and therefore already planned for laparoscopic biliary intervention. A randomized trial of laparoscopic cholecystectomy plus laparoscopic common bile duct exploration vs laparoscopic cholecystectomy plus ERCP (in patients with normal foregut anatomy) for management of common bile duct stones suggested comparable efficacy and a shorter hospital stay with the purely surgical approach (25). The laparoscopic approach to common bile duct stones and avoidance of LATE also eliminates potential patient exposure to PEP.

Future considerations

Contemporary treatment of obesity features both medical and surgical treatment options, and roles will continue to evolve even for established therapies. Among patients who undergo surgical management, recent data suggest an increasingly prevalent approach of sleeve gastrectomy (which preserves standard peroral endoscopic access to the papilla) rather than gastric bypass (26). Endoscopic treatment options include intragastric balloon placement or endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty. Prescription of semaglutide as weight loss therapy has increased several hundred percentage points in short order, with more than 9 million prescriptions written in the United States within the last 3 months of 2022 (27).

Yet irrespective of the volume of future RYGB performed as compared with alternative surgical or medical treatments, there exists a sizable cohort of patients who have undergone prior RYGB and who are at jeopardy of need for ERCP even decades post-operatively. And while the majority of LATE are currently being performed for management of stone disease, one can expect that as the cohort of RYGB ages, and given the association between obesity and pancreatic cancer, there will be an increasing incidence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma requiring endoscopic diagnosis and palliative endoscopic therapy. Laparoscopic transgastric access to the duodenum for EUS/ERCP could remain an important option in the setting of suspected pancreatic neoplasm involving the pancreatic head, and potentially include the advantage of offering simultaneous staging laparoscopy to exclude occult peritoneal or abdominal metastasis.

Finally evolution of technology and training paradigms may impact the performance of LATE. For instance, with the emergence of robotic surgical platforms and their dissemination into surgical training programs only a minority of surgical trainees may report thorough or satisfactory experiences in laparoscopic training techniques (28). This trend may on the one hand undermine development of laparoscopic skills necessary for successful performance of LATE, yet on the other hand provide future opportunity for incorporation of robotic techniques in surgically-assisted ERCP.

Conclusions

A sizable number of patients who have undergone RYGB will someday present with either benign or malignant pancreatobiliary disease requiring ERCP. LATE offers an effective, established, low-morbidity option for intervention and clinical management. Optimal collaboration between the surgical and endoscopic teams performing LATE requires a clear understanding of appropriate procedural indications, application of sound surgical and endoscopic techniques, ability to recognize and manage post-procedural adverse events, and consideration of alternative interventional options when appropriate. While the logistics, resources, and complexity of LATE may seem cumbersome relative to performance of ERCP in the setting of normal foregut anatomy, the invested effort in performance of LATE can result in highly successful and desirable patient outcomes. Future trends in surgical or non-surgical management of obesity, disruptive surgical and endoscopic techniques, and epidemiologic trends in disease presentation are likely to further influence and refine the role of LATE.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-24-6/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-24-6/coif). P.Y. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery from October 2023 to September 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stierman B, Afful J, Carool MD, et al. national Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files—Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports, 2021, No. 158. MD: National Center for Health Statistics 2021.

- Adult Obesity Facts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html (Accessed October 18, 2023)

- Ward ZJ, Bleich SN, Long MW, et al. Association of body mass index with health care expenditures in the United States by age and sex. PLoS One 2021;16:e0247307. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clapp B, Ponce J, DeMaria E, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2020 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;18:1134-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiffman ML, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, et al. Gallstone formation after rapid weight loss: a prospective study in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery for treatment of morbid obesity. Am J Gastroenterol 1991;86:1000-5. [PubMed]

- Guadalajara H, Sanz Baro R, Pascual I, et al. Is prophylactic cholecystectomy useful in obese patients undergoing gastric bypass? Obes Surg 2006;16:883-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wanjura V, Sandblom G, Österberg J, et al. Cholecystectomy after gastric bypass-incidence and complications. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2017;13:979-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel KR, White SC, Tejirian T, et al. Gallbladder management during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: routine preoperative screening for gallstones and postoperative prophylactic medical treatment are not necessary. Am Surg 2006;72:857-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuller W, Rasmussen JJ, Ghosh J, et al. Is routine cholecystectomy indicated for asymptomatic cholelithiasis in patients undergoing gastric bypass? Obes Surg 2007;17:747-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dorman RB, Zhong W, Abraham AA, et al. Does concomitant cholecystectomy at time of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass impact adverse operative outcomes? Obes Surg 2013;23:1718-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Worni M, Guller U, Shah A, et al. Cholecystectomy concomitant with laparoscopic gastric bypass: a trend analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample from 2001 to 2008. Obes Surg 2012;22:220-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abbas AM, Strong AT, Diehl DL, et al. Multicenter evaluation of the clinical utility of laparoscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1031-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim CH, Jahansouz C, Freeman ML, et al. Outcomes of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and Sphincterotomy for Suspected Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction (SOD) Post Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes Surg 2017;27:2656-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- AlMasri S, Zenati MS, Papachristou GI, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted ERCP following RYGB: a 12-year assessment of outcomes and learning curve at a high-volume pancreatobiliary center. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(1):621-630. Correction appears in Surg Endosc 2022;36:631.

- Saleem A, Levy MJ, Petersen BT, et al. Laparoscopic assisted ERCP in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:203-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Falcão M, Campos JM, Galvão Neto M, et al. Transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for the management of biliary tract disease after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass treatment for obesity. Obes Surg 2012;22:872-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Tarazi M, et al. Procedural Outcomes of Laparoscopic-Assisted Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Patients with Previous Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2021;31:282-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohammad B, Richard MN, Pandit A, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted ERCP in gastric bypass patients at a community hospital center. Surg Endosc 2020;34:5259-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ali MF, Modayil R, Gurram KC, et al. Spiral enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in bariatric-length Roux-en-Y anatomy: a large single-center series and review of the literature (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:1241-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sato T, Nakai Y, Kogure H, et al. ERCP using balloon-assisted endoscopes versus EUS-guided treatment for common bile duct stones in Roux-en-Y gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc 2024;99:193-203.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shinn B, Boortalary T, Raijman I, et al. Maximizing success in single-session EUS-directed transgastric ERCP: a retrospective cohort study to identify predictive factors of stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc 2021;94:727-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Runge TM, Chiang AL, Kowalski TE, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE): a retrospective multicenter study. Endoscopy 2021;53:611-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prakash S, Elmunzer BJ, Forster EM, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE): a systematic review describing the outcomes, adverse events, and knowledge gaps. Endoscopy 2022;54:52-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghandour B, Keane MG, Shinn B, et al. Factors predictive of persistent fistulas in EUS-directed transgastric ERCP: a multicenter matched case-control study. Gastrointest Endosc 2023;97:260-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, et al. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg 2010;145:28-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Welbourn R, Hollyman M, Kinsman R, et al. Bariatric Surgery Worldwide: Baseline Demographic Description and One-Year Outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018. Obes Surg 2019;29:782-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilbert D. Prescriptions for Ozempic and similar drugs have skyrocketed, data shows. The Washington Post, September 27, 2023. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/27/ozempic-prescriptions-data-analysis/

- Duchene DA, Moinzadeh A, Gill IS, et al. Survey of residency training in laparoscopic and robotic surgery. J Urol 2006;176:2158-66; discussion 2167. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Yachimski P, Guggilapu S, Poulose B. Laparoscopic-assisted transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a review of indications, technical considerations, and outcomes. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2024;9:26.