Being critical of the critical view of safety: alternate approach in the armamentarium for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Highlight box

Key findings

• A total of 1,868 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were done using posterior infundibular technique.

• The technique is safe and there were no bile duct injuries.

What is known and what is new?

• In instances of difficult anatomy, stepwise dissection to achieve the three criteria of the critical view of safety is challenging.

• Posterior infundibular technique can be adapted for difficult gallbladders.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• A surgeon should be facile with different approaches during cholecystectomies.

IntroductionOther Section

Critical view of safety (CVS)

The concept of CVS for anatomic identification was first described by Strasberg in 1992 (1) [term mentioned in 1995 (2)] and has been widely adopted by surgeons with the goal of perform safe laparoscopic (and now robotic) cholecystectomy. Originally, in open cholecystectomy, two structures were identified after the gallbladder is taken off the fossa. In laparoscopic surgery, to facilitate the easier clipping of the cystic duct and cystic artery, as a modification, only the lower part of the gallbladder needed to be taken off the fossa. Surgeons-in-training had widely been taught that three criteria are required to achieve CVS: (I) hepatocystic triangle (cystic duct, common hepatic duct, and inferior edge of liver) must be cleared of fat and fibrous tissue, (II) the lower third of the gallbladder must be separated from the liver to expose the cystic plate, and (III) two structures (and only two structures) must be seen entering the gallbladder (3).

Flaws in the CVS

Although following the steps to achieve CVS as outlined above has become the standard teaching in performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there are still shortcomings, and common bile duct (CBD) injuries still occur. In a systematic review of over 10,000 cases, CVS-related CBD injury was 0.09%, with half of the injuries being due to technical errors and half due to structural misidentification (4).

One flaw in the application of CVS is the misconception that if the CVS is achieved, there is no bile duct injury. Potentially, the dissection steps taken to achieve the view of “two structures entering the gallbladder” may have already led to CBD injury without real-time recognition. As affirmed by Strasberg, “CVS is not a method of dissection but a method of target identification (5).” The CVS “was conceived not as a way to do laparoscopic cholecystectomy” but as an application to help “avoid biliary injury (5)”. CVS can attest to correct identification after dissection has taken place. It does not prevent biliary injury, just as the application of intra-operative cholangiogram can confirm biliary anatomy after dissection is mostly done, and not necessarily prevent biliary injury.

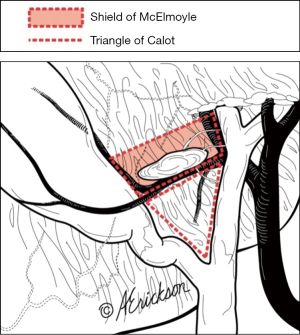

In instances of inflamed and fibrosed hepatocystic triangle, persistence in trying to achieve the three criteria of the CVS can lead to biliary and vascular injuries. The peritoneum that covers the cystic duct and part of the body, infundibulum and neck of the gallbladder is called the “Shield of McElmoyle” (Figure 1), which was first described in 1954 (6), and later rediscussed (7). Dissection over this area is not recommended when it is “hostile and inflamed (7)”. Thus, in this instance, step 1 of CVS cannot be achieved.

There are other instances in which the three criteria of CVS cannot be met. These include cases with aberrant hepatic ducts, contracted gallbladder, stone impaction or fibrosis at the neck. Prominent posterior cystic arteries also challenge step 3 of CVS where “only two structures” must be seen entering the gallbladder.

Thus, in instances of difficult anatomy, where the stepwise dissection to achieve the three criteria of CVS cannot be done, other approaches should be available in the armamentarium of laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The 2020 SAGES guidelines summarized that there was no evidence “to support CVS over other methods for anatomic identification (8)”. Here we present safety data using an alternate approach: posterior infundibular dissection. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-62/rc).

MethodsOther Section

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This research paper was exempt from NYU Langone Health institutional review board (IRB) approval, as the project was not research involving human subjects and did not require IRB review. Informed consent was not required. Retrospective review was done on all laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed from January 2010 to July 2023 by one surgeon (G.F.) at NYU Langone Hospital - Brooklyn and Staten Island University Hospital. The technique used was posterior infundibular dissection. This technique is distinct from the “classical” infundibular technique that is often mentioned in the literature (9,10). Demographic data included sex, age, elective vs. non-elective case type, biliary complications and conversion to open. Primary outcome was biliary complications. There was no missing data. No advanced statistical analysis was done, and only range and proportion were reported where applicable.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy using posterior infundibular dissection approach as an alternative to CVS

This method was previously described by our team, Iskandar et al. (11). In summary, this method accomplishes circumferential dissection of the infundibulum, and drops the cystic artery medially as opposed to skeletonizing it (Figures 2,3). Thus, even in very inflamed situation, this method is safe. It allows for preservation of the area which we had termed the “trapezoid of no-dissection”, which is bounded by the common hepatic duct medially, the node of Lund inferiorly, the anterior cystic artery laterally and the inferior margin of the liver superiorly (Figures 4,5). Coincidentally, the “trapezoid of no-dissection” is also the area that is covered by the Shield of McElmoyle. In cases of normal anatomy and minimal inflammation, using either CVS technique or posterior infundibular dissection approach yields similar results as the structures can be easily identified, safely dissected and clipped.

Technical pearls of posterior infundibular dissection approach

There are several benefits to the posterior infundibular dissection approach as described here. One benefit of circumferential 360-degree skeletonization of distal gallbladder and infundibulum is that this step-wise approach uncoils the folded infundibulum at the cystic duct junction. This approach is safe in the presence of hidden cystic duct. In the same vein, this technique is safe in cases of aberrant hepatic ducts, as all the potential aberrant anatomy tends to concentrate within the “trapezoid of no-dissection”. In cases of fibrosis at the neck or when requiring “top-down” dissection, avoidance of the trapezoid is also recommended for safe dissection (Figure 6), to avoid the “error trap” that the right hepatic artery can be retracted caudad with the gallbladder in cases of inflammation (12).

ResultsOther Section

From January 2010 to July 2023, one surgeon (G.F.) performed 1,868 laparoscopic cholecystectomies using posterior infundibular dissection approach. Of these cases, 18% (336/1,868) were non-elective, 77% (1,438/1,868) were female, and their age ranged from 15 to 90 years. Mean duration of procedure was 38 minutes. Subtotal cholecystectomies were performed on 1% (24/1,868) of the cases, one case was converted to open, and there were four cases of cystic stump leak, but no bile duct injuries. One case required intraoperative cholangiogram to confirm identification of right sectoral duct. Of the 24 subtotal cholecystectomies, there were three fenestrated subtotal cholecystectomies, and one partial cholecystectomy due to severe inflammation and frozen anatomy. This patient underwent completion open cholecystectomy 3 months later. The rest were non-reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomies with drains, which were subsequently removed after monitoring for any persistent leak, of which there were none. All subtotal cholecystectomies were non-elective cases. On some occasions, top down or dome-down techniques were used, but followed the caveat as described in Figure 6.

DiscussionOther Section

We presented 1,868 cases from one surgeon’s (G.F.) 13-year experience, without bile duct injury. With this approach, we avoided dissection over the Shield of McEmoyle, a potential hotbed for aberrant anatomy. Our data shows that the posterior infundibular dissection technique is a safe alternative for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

In fact, in 2017, Strasberg has also stated that “CVS is not the only method within the standard of care” and that “many surgeons in practice use and are confident in other methods (13)”. In a systematic review based on 90 studies looking at laparoscopic cholecystectomies, the authors concluded that it was impossible to recommend a method over others to prevent biliary injury, but that surgeons should place emphasis on appropriate dissection techniques (14). Nassar et al. [2021] (15) summarized it best in their study that “CVS is a conclusion of the dissection process” and that “it would be unusual that injuries of the main bile ducts would occur after displaying the CVS, although the description of CVS does not focus on how to achieve this endpoint”. We agree with their assessment that as it becomes paramount to achieve all the components of CVS, it is more difficult to accomplish (15). The persistence of the surgeon to establish the CVS at this point may become harmful.

A surgeon knows early on which case could be a challenging gallbladder. Predictors of not being able to establish CVS include significant adhesions, accessory cystic artery, contracted gallbladders and those with Hartmann’s pouch stones (15). Thus in safe cholecystectomy, surgeons must know when to adjust techniques when cases are not routine and when to bail out (16).

Bile duct injuries are mostly due to misidentifying anatomy because of severe inflammation (17). Understanding landmarks is crucial. When the gallbladder is lifted cephalad, the inferior border of safe dissection is a diagonal line drawn from Rouviere’s sulcus to lower edge of segment 4 (17,18). If starting too low, attempts to adhere to CVS and misidentification of “two structures” can happen (18). Anatomic variations including right hepatic artery or another third structure in Calot’s triangle (19) or the presence of several branches of cystic artery contribute to potential injuries (17,20). During the dissection, recognizing the different potential insertion points of cystic duct is also important as it can insert high, low-posterior, or can be short “hidden” duct (9,11,17).

Dissection techniques can be modified to achieve safe cholecystectomy. Sometimes, the view and dissection can be further optimized when the artery is clipped and transected first and helps with better identification of the cystic duct (21). Posterior infundibular dissection technique as described in this study is safe alternative, as it avoids the “trapezoid of no-dissection” and the structures covered by the Shield of McElmoyle, and can be safely applied to challenging gallbladders and cases with aberrant anatomy. Intraoperative adjuncts including intraoperative cholangiogram and indocyanine green also help identify vascular and biliary structures (22). In these cases, gallbladder can still be safely dissected, just not via what is typically described in the 3-step CVS technique.

Thus, the idea that subtotal cholecystectomy is recommended when CVS cannot be achieved is over-simplified. CVS is a safe starting point, but with a hostile gallbladder, other dissection techniques and algorithms can and should be applied. However, any technique will have its shortcomings, and the posterior infundibular technique will also be limited by difficult anatomy such as cemented or frozen or porcelain-like gallbladder, as we have also experienced in 1% of our cholecystectomies, all of which were non-elective cases. If at any point, the surgeon thinks moving forward to dissect out the cystic duct will cause injury, then they should consider subtotal fenestrated cholecystectomy or other bail-out techniques (18). The decision is not a light one, as they are associated with high peri-operative morbidity (23).

One of the limitations of this study is that it is a retrospective review and data is from one surgeon (G.F.). As G.F. has been utilizing this alternative dissection method for over 1 decade, and has good safety profile, there is bias in preference for this method. However, the goal of this study was not to show superiority of this method over other methods of dissection during cholecystectomy such as CVS. On the contrary, the senior author wished to present safety data and impart to the readers an alternative dissection technique.

ConclusionsOther Section

Posterior infundibular dissection is a safe alternative approach to cholecystectomy. The foundation of this technique is the understanding of anatomy. We avoid initiating the dissection within the Shield of McElmoyle. This becomes more relevant when the hepatocystic area is hostile, and the boundaries cannot be clearly defined, as all the potential aberrant anatomy tends to concentrate within the “trapezoid of no-dissection”.

AcknowledgmentsOther Section

The abstract for this manuscript was presented as a poster at SAGES 2023 Annual Meeting, entitled “Is the Critical View of Safety Flawed?”

Funding: None.

FootnoteOther Section

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-62/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-62/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-62/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-62/coif). G.F. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery from April 2023 to March 2025. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This research paper was exempt from NYU Langone Health institutional review board (IRB) approval, as the project was not research involving human subjects and did not require IRB review. Informed consent was not required.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

ReferencesOther Section

- Strasberg SM, Sanabria JR, Clavien PA. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Surg 1992;35:275-80. [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180:101-25. [PubMed]

- Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) safe cholecystectomy program. Available online: www.sages.org/safe-cholecystectomy-program

- Manatakis DK, Antonopoulou MI, Tasis N, et al. Critical View of Safety in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Systematic Review of Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. World J Surg 2023;47:640-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM. A perspective on the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2017;2:91. [Crossref]

- McElmoyle WA. Cholecystectomy: a method for the difficult gall-bladder. Lancet 1954;266:1320-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pran L, Maharaj R, Dan D, Baijoo S. McElmoyle's Shield Revisited. J Am Coll Surg 2017;225:349-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, et al. Safe Cholecystectomy Multi-society Practice Guideline and State of the Art Consensus Conference on Prevention of Bile Duct Injury During Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 2020;272:3-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM, Eagon CJ, Drebin JA. The "hidden cystic duct" syndrome and the infundibular technique of laparoscopic cholecystectomy--the danger of the false infundibulum. J Am Coll Surg 2000;191:661-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesce A, Palmucci S, La Greca G, et al. Iatrogenic bile duct injury: impact and management challenges. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2019;12:121-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iskandar M, Fingerhut A, Ferzli G. Posterior infundibular dissection: safety first in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2021;35:3175-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM. Error traps and vasculo-biliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2008;15:284-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. The Critical View of Safety: Why It Is Not the Only Method of Ductal Identification Within the Standard of Care in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 2017;265:464-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van de Graaf FW, Zaïmi I, Stassen LPS, et al. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A systematic review of bile duct injury prevention. Int J Surg 2018;60:164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nassar AHM, Ng HJ, Wysocki AP, et al. Achieving the critical view of safety in the difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study of predictors of failure. Surg Endosc 2021;35:6039-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos BF, Brunt LM, Pucci MJ. The Difficult Gallbladder: A Safe Approach to a Dangerous Problem. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2017;27:571-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mischinger H, Wagner D, Kornprat P, et al. The “critical view of safety (CVS)” cannot be applied – What to do? Strategies avoid bile duct injuries. Eur Surg 2021;53:99-105. [Crossref]

- Deng SX, Greene B, Tsang ME, et al. Thinking Your Way Through a Difficult Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Technique for High-Quality Subtotal Cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2022;235:e8-e16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi R, Ignjatovic D. More than two structures in Calot's triangle. A postmortem study. Surg Endosc 2000;14:354-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesce A, Fabbri N, Feo CV. Vascular injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: An often-overlooked complication. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023;15:338-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wijsmuller AR, Leegwater M, Tseng L, et al. Optimizing the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy by clipping and transecting the cystic artery before the cystic duct. Br J Surg 2007;94:473-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bertani C, Cassinotti E, Della Porta M, et al. Indocyanine green—a potential to explore: narrative review. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2022;7:9. [Crossref]

- Lucocq J, Hamilton D, Scollay J, et al. Subtotal Cholecystectomy Results in High Peri-operative Morbidity and Its Risk-Profile Should be Emphasised During Consent. World J Surg 2022;46:2955-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Hoang CM, Ferzli G. Being critical of the critical view of safety: alternate approach in the armamentarium for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2024;9:21.