Laparoscopic surgical treatment for recurrent gastroesophageal reflux disease

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common diagnosis in North America with a prevalence of up to 40% in the United States (1). While the majority of individuals diagnosed with GERD are treated medically, an increasing number of individuals are presenting for surgical treatment due to refractory symptoms or unsatisfactory side effect profiles of anti-reflux medications. The current gold standard antireflux procedure is the laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with many reports heralding its efficacy in the setting of low procedure-associated morbidity (2). Subjective improvement in heartburn and atypical symptoms are observed in over 90% of patients, and 80–90% of patients have normal pH studies after surgery (3). Additionally, mid- and long-term satisfaction rates are as high as 94% after surgery (1,2,4).

Despite impressive long-term results, a number of patients will fail after anti-reflux surgery. Published rates vary largely due to the lack of consensus regarding the definition of failure. There are published reports that over 50% of patients resume anti-reflux medications with little objective evidence that pathologic reflux is to blame for the recurrent symptoms (1). Conversely, objective evidence of abnormal esophageal acid exposure has been reported in 5–17% of patients. Interestingly, these findings do not often correlate well with symptoms (5). Surgical failure can also be defined objectively by advanced imaging or endoscopy. Utilizing a strict definition of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) moving 2 cm above the diaphragm on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series, Oelschlager et al. noted a >50% 5-year recurrence rate after paraesophageal hernia repair with fundoplication (6). Unfortunately, recurrence of hiatal hernia or wrap disruption also has poor correlation with patient symptoms (5). Regardless, 5–10% of patients will eventually undergo reoperative surgery for new, recurrent or unchanged symptoms of GERD (2).

Presentation and etiology of failed anti-reflux operations

The evaluation of a patient referred for consideration of surgical intervention after prior antireflux surgery is complex. In deciding whether a patient is a good candidate for surgical reintervention it is critical to identify whether they possess any high-risk factors that have led to their presentation. The presence of these risk factors helps to counsel the patient (potentially away from surgery), aid in surgical decision making and help guide preoperative diagnostic testing.

Certain individuals presenting as surgical failures were at high risk for low satisfaction after their primary antireflux surgery and remained at high risk for dissatisfaction after a redo operation. These risk factors include poor response to medical acid suppression, atypical symptoms (cough, hoarseness, etc.) or a normal preoperative pH study (1,2). These patients may present as surgical failures with or without objective evidence of inappropriate anatomy. Individuals who were improperly selected for antireflux surgery may present with persistent or worsening symptoms since surgery. This should be strongly considered in the setting of normal or expected postoperative anatomy (1,2). This population necessitates a thoughtful evaluation for other GI pathologies such as achalasia, motility disorders, and malignancy. Alternatively, in those patients who were properly evaluated with classic indications for surgical intervention, risk factors for failure include poor esophageal peristalsis, large hiatal hernia, older age, female gender, obesity, and chronic gagging, retching or vomiting (1,2). These risk factors also increase the risk of a second anti-reflux operation and need to be considered while counseling the patient.

The most common symptoms that lead to reoperative surgery are recurrent GERD and dysphagia (3,5,7-10). In two large systematic reviews, the most commonly reported indication for reoperation was recurrent GERD (59.4% and 61%) followed by dysphagia (30.6% and 31%). Other indications for surgery including hiatal hernia, chest pain, vomiting and gas bloat were much less common (5,7). These reviews determined that anatomical recurrence is actually a rare primary indication for revision surgery as are more atypical symptoms such as chest pain, gas bloat, and vomiting and that the main driver for redo surgery is GERD and dysphagia (5,7).

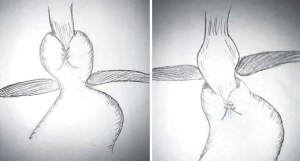

Patients with true surgical failures presenting with symptoms of recurrent GERD or dysphagia will usually have a technical or anatomic explanation for their presentation. This is most often noted in the individual who describes initial symptomatic benefit followed by a gradual or sudden development of recurrent symptoms. A variety of technical failures can be observed and usually involve an incorrectly constructed fundoplication. Patients can present with a fundoplication that was too tightly constructed, was made with a twisted orientation or was positioned incorrectly over the body of the stomach rather than the distal esophagus (3,5,7-10). If the hiatal closure is too tight the patient may be present with a hiatal stenosis. Anatomical failures include a fundoplication that has slipped caudally with telescoping of the stomach through the wrap or with the entire fundoplication herniating above the diaphragm (Figure 1). Patients may also present with a wrap that is positioned correctly below the hiatus but have developed a new true paraesophageal hernia. In addition, the wrap itself may have become disrupted (3,5,6,8-10).

The most commonly reported operative finding during redo surgery is an intrathoracic wrap migration. This finding is closely followed in frequency by wrap disruption and a slipped fundoplication (7,8). Other causes of failure such as a tight fundoplication, or an incorrectly positioned wrap are less common. Intrathoracic wrap migration and a slipped wrap accounted for 54% of the failures observed at surgery overall. Patients with a slipped wrap or intrathoracic wrap migration are more likely to present with recurrent heartburn whereas a patient with a paraesophageal hernia or other cause of failure is more likely to present with dysphagia (3,11). It is not uncommon for multiple anatomic failures to be observed in a single patient.

Pre-operative assessment

The evaluation of a patient referred for a possible breakdown of an anti-reflux surgery needs to be completed with the most common etiologies in mind. Specifically, prior to considering a revisional surgery, a careful review of the patient’s work up preceding the index operation needs to be performed. A number of diagnoses including eosinophilic esophagitis, functional heartburn or esophageal hypersensitivity, malignancy and achalasia may mimic GERD. In addition, other functional disorders of the foregut such as esophageal dysmotility and gastroparesis may present with a constellation of symptoms consistent with a failed antireflux procedure. In reality, these cases represent poor initial patient selection, incomplete preoperative workup or post-operative complications (1,2). A meticulous review of imaging and investigations prior to the index surgery may provide clues as to the cause of the presenting symptoms. An examination of the operative notes paying close attention to the size of the hernia defect, whether the short gastric vessels were divided, length of intraabdominal esophagus achieved, type of fundoplication, use of mesh or pledgets all give clues to and allow for proper operative planning.

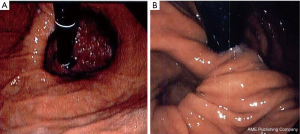

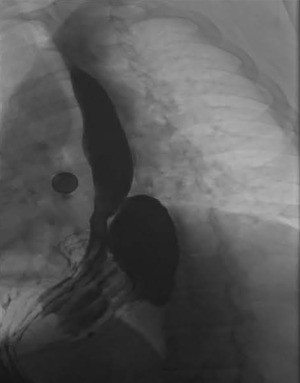

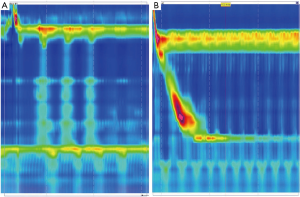

In general, upper endoscopy and esophagram are performed in all patients to help delineate anatomy and evaluate for hiatal hernia. Endoscopy also allows for the evaluation of esophageal mucosa including assessment for eosinophilic or candida esophagitis, changes concerning for Barrett’s or malignancy. In addition, an endoscopy allows for a visual impression of a tight, malpositioned or slipped wrap (Figure 2). An UGI series allows for further characterization of the anatomy and emptying of the esophagus (Figure 3). Objective pH testing should also be performed to confirm pathologic acid exposure. Completion of testing while taking proton pump inhibitors can give valuable information on proper acid suppression and help counsel the patient on the relationship between his or her symptoms and the presence of pathologic levels of acid in the esophagus. Evaluation with high-resolution esophageal manometry (HREM) should be performed to assess for the strength and coordination of the esophageal contractions in all patients being considered for revisional surgery. The results of an HREM can help risk stratify for post-op dysphagia as well as ensure that there is no intrinsic dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) (Figure 4). Finally, in the setting of symptoms concerning for bloating, a gastric emptying study may demonstrate severe gastroparesis which should lead the surgeon to consider pyloroplasty or Roux-en-Y conversion (2).

Operative tenets

Redo antireflux operations require a significant skill. Historically, these procedures were performed via laparotomy or thoracotomy for optimized exposure. More recent publications have established the safety and efficacy of a laparoscopic approach (11-13). The laparoscopic approach allows for decreased wound-related morbidity, postoperative pain and time for convalescence (3,5,7,8). Angled laparoscopes allow for excellent visualization of the challenging to reach hiatus and allow for high mobilization of the esophagus in the mediastinum.

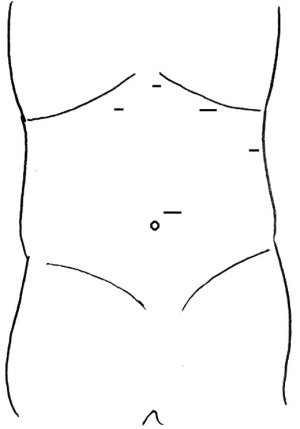

If redo fundoplication is selected as the surgery of choice, a takedown of the previous repair and fundoplication is compulsory. The patient is placed in a modified lithotomy position, and the surgeon stands between the legs. A total of 5 trocar sites are used including a camera port, an assistant port and two operative ports (Figure 5). An epigastric puncture for a Nathanson liver retractor or a 5th trocar can be used for a flexible liver retractor through the right lateral abdominal wall. Initially, adhesiolysis is performed to reflect the liver and expose the hiatus. At this point, the hiatus can be approached from the patient’s right or left side. A right-sided approach starts by incising the remnant pars flaccida to the level of the right crus. The right crus is then freed from the hernia sac at this location, carrying the dissection superiorly and towards the left crus. At this point, the esophagus, stomach, and wrap should become apparent. Dissection can then be continued on the left side towards the crural confluence caudally. Dense adhesions may be encountered throughout this dissection. The old permanent suture may act as a guide for dissection and should be cut and removed to aid in visualization. In addition, old mesh that is encountered should be removed if possible. Once the extent of the right-sided dissection is complete attention can be turned to the left side. Short gastric vessels are divided up the level of the left crus, and the hernia sac is freed to meet up with dissection plane started from the right. A retroesophageal window can then be created, and a Penrose drain passed to aid in retraction. Extensive mediastinal dissection is then performed to gain esophageal length. At this point, the wrap must be taken down to return the stomach to the native anatomy. Careful blunt dissection should be performed to develop the plane between the wrap and the stomach or esophagus. Alternatively, if a tunnel is created under the approximated fundus, a linear stapler can be used to divide the wrap. The entire process and dissection are facilitated by internal verification of anatomy with intraoperative endoscopy.

Once the stomach has been returned to native anatomy, and esophageal mobilization is complete it is prudent to review the operative findings to ensure that the factors that led to failure during the primary operation are addressed. Common issues to be addressed include an adequate length of the esophagus, complete mobilization of the fundus with a division of the short gastric vessels, careful and accurate identification of the GEJ or proper wrap placement and careful assessment of the Cura and size of the defect to be closed. When assessing the crural pillars and the hernia defect consideration for the use of absorbable mesh or pledgeted sutures can be made. While no robust evidence exists for the use of either in redo antireflux surgery the literature does suggest that use of mesh or pledgets in hiatal hernia repair may reduce early recurrence (14,15). It should be noted that no long-term decrease in recurrence or necessity of reoperation has been shown with the use of mesh in primary hiatal hernia repair (16). With that said, it can be considered as an adjunct or tool in repairing the recurrent hiatal defect (14,15). Consideration and caution should be used with the use of permanent mesh given the reported risk of mesh induced stenosis and mesh migration. In the event that the crura inadequately re-approximate without tension, a relaxing incision in the right crus with or without mesh reinforcement can be completed.

Incidence of the short esophagus is much greater in reoperative antireflux surgery, and the surgeon must be facile with a Collis wedge gastroplasty should there be persistent inadequate esophageal length after extensive mediastinal mobilization. Alternatively, evidence suggests that additional length can be achieved with ligation of the vagus nerve without significant associated gastric atony (17). Careful identification of the GEJ should be performed endoscopically and after resection of the hernia sac to ensure proper wrap placement. The complete short gastric division allows for proper wrap creation and placement without tension. The type of fundoplication created should be made based on patient discussions. A complete fundoplication will provide a durable reflux barrier, but with an increased side effect profile. Conversely, a 270-degree Toupet fundoplication will have an improved side effect profile, but perhaps at the sacrifice of fundoplication durability. Nonetheless, a compelling argument can be made for the use of a partial fundoplication in the setting of severe dysphagia and esophageal motility disorders.

Outcomes of revisional anti-reflux surgery

Revision surgery is challenging with reported operative times, length of hospital stays and patient morbidity being significantly higher than that of primary operations. That being said, reported outcomes from reoperative surgery are relatively good (3,5,7,8). A review of 176 cases of re-interventions for failed antireflux surgery was performed by Khajanchee et al. (13). They found that 74.5% of patients experienced excellent subjective outcomes and that rate of improvement on objective pH monitoring was 74.2%. Using regression analysis, the presence of preoperative dysphagia and need for a Collis gastroplasty were independent risk factors for a re-operative failure. A large review performed by van Beek et al. noted an intraoperative complication rate of 18.6% with the most common complication being inadvertent gastrointestinal perforation (5). Notably, this rarely led to long-term morbidity and average success rates after surgery were 81%. A comprehensive review performed by Symons et al. demonstrated mean success rates of 84% and an overall complication rate of 14% (8). Peri-operative mortality rates in most series are reported as being less than 1%.

Long-term positive results after redo surgery decrease with time but are still encouraging. A retrospective study by Oelschlager and colleagues addressed the long-term success of reoperative surgery (18). They identified 41 patients with a median follow-up of 50 months. In this cohort, 68% reported excellent or good results and 78% reported being pleased with their decision to undergo reoperation. Improvement in heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia was observed in 61%, 69%, and 74% respectively at a median of 50 months. In addition to symptomatic improvement, patients who undergo redo fundoplication experience measured improvement in disease-specific quality of life (19).

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) as a revision procedure

In individuals with a BMI >35 strong evidence exists as to the effectiveness of a RYGB in both resolving GERD as well as managing morbid obesity and the associated comorbidities. In addition, individuals who have significant gastroparesis or delayed gastric emptying should also be considered for conversion to Roux-en-Y anatomy. A retrospective study performed by Yamamoto et al. comparing the long-term outcomes between redo fundoplication and Roux-en-Y in patients with failed fundoplications mean satisfaction rates were as high as 87% (20). There was no statistically significant difference in satisfaction between the two procedures. However, patients with a BMI over 35 had better symptom improvement after gastric bypass and significantly greater weight loss. Further, in patients with four or more high-risk factors (BMI >35, ≥2 previous surgeries, esophageal dysmotility, delayed gastric emptying, dysphagia, respiratory symptoms, short esophagus) better symptom outcomes were seen after gastric bypass compared to redo fundoplication. Additionally, in patients with esophageal dysmotility, postoperative dysphagia was higher in those who underwent redo fundoplication versus a Roux-en-Y. The conclusion of this study was that, while redo fundoplication and Roux-en-Y are both good options after failed anti-reflux surgery, the Roux-en-Y should be considered the preferred operation in patients with morbid obesity, esophageal dysmotility, and more complex pathology.

While outcomes are relatively good for redo antireflux surgery, a small percentage of these procedures will also fail. This number is reported to be as high as 10% (5). Unfortunately, the satisfaction rate after a third antireflux surgery is only 42% (21). In lieu of performing the third fundoplication, consideration should be made to converting the patient to Roux-en-Y anatomy. As is widely reported in the bariatric literature, a Roux-en-Y largely separates the acid-producing parietal cells from the esophagus. In addition, obesity is an established risk factor for reflux disease and decreases in excess body weight improves reflux symptoms (22). Finally, individuals with dysphagia and esophageal dysmotility have better symptomatic outcomes following Roux-en-Y compared to redo fundoplication (20). Little data exists regarding outcomes after a third or greater antireflux operation. Awais et al. reported on 25 patients who underwent conversion to Roux-en-Y for recurrent GERD after antireflux surgery (23). In that cohort, 44% had undergone more than one prior reflux operation. Satisfaction rates in those with two or more prior antireflux surgeries were reported to be 80%. Roux-en-Y can also be safely used in non-obese individuals with high overall satisfaction (24). Roux-en-Y should be strongly considered as an esophagus salvage procedure as esophagectomy is occasionally performed after multiple failed redo antireflux operations.

When conversion to a Roux-en-Y is selected, the patient is prepped and positioned as is usual for a gastric bypass. Additional ports or altered port placement is often required to facilitate a more difficult hiatal dissection and adhesiolysis. In the setting of a recurrent hiatal hernia, access to the mediastinum is achieved with esophageal mobilization to reduce the stomach into the peritoneal cavity in a similar manner to what would be done with a concomitant repeat fundoplication. Following this, a Roux-en-Y can be completed according to the operative surgeon’s preference. In the setting of a disrupted or ineffective wrap, the decision to take down the fundoplication is not mandatory as the diversion of the acid should address the symptoms associated with the pathologic acid exposure. In this situation, the risk of a wrap takedown must be weighed against any small potential benefit given the risk of gastroesophageal injury. In the event that an appropriately sized pouch can be made, it may be advisable to leave the wrap in place rather than risk injury.

Conclusions

Antireflux surgery has a high success rate with an excellent safety profile. Fortunately, reoperative antireflux surgery is required in a minority of patients. In those patients, great care must be taken to evaluate the patient to ensure a complete workup has been performed. Every attempt should be made to elucidate the cause of failure of the index operation as well as whether or not the initial operation was clinically indicated. At the time of the operation, every effort should be made to return the stomach to its native position and adequately mobilize the esophagus with or without a Collis gastroplasty. A technically sound hiatal repair and an appropriately selected fundoplication based on the patient’s symptoms and esophageal function is essential. In individuals who are obese, have dysphagia, multiple risk factors, gastroparesis or who have had two or more attempts at antireflux surgery strong evidence exists for the conversion of these individuals to Roux-en-Y anatomy. Overall, morbidity rates are high in reoperative antireflux surgery; however, when performed correctly by experienced surgeons revision surgery can impart significant symptom and quality of life improvement.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Muhammed Ashraf Memon and Abe Fingerhut) for the series “Laparoendoscopic Surgery for Benign Oesophagogastric Conditions” published in Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ales.2019.05.12). The series “Laparoendoscopic Surgery for Benign Oesophagogastric Conditions” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Grover BT, Kothari SN. Reoperative antireflux surgery. Surg Clin North Am 2015;95:629-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ulualp K, Gould JC. Reoperative Surgery for Failed Antireflux Procedures. In: Oleynikov D, Fisichella PM, editors. A Mastery Approach to Complex Esophageal Diseases. Berlin: Springer, 2018:35-47.

- Hatch KF, Daily MF, Christensen BJ, et al. Failed fundoplications. Am J Surg 2004;188:786-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson B, Dunst CM, Cassera MA, et al. 20 years later: laparoscopic fundoplication durability. Surg Endosc 2015;29:2520-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Beek DB, Auyang ED, Soper NJ. A comprehensive review of laparoscopic redo fundoplication. Surg Endosc 2011;25:706-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oelschlager BK, Petersen RP, Brunt LM, et al. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: defining long-term clinical and anatomic outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:453-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furnée EJ, Draaisma WA, Broeders IA, et al. Surgical reintervention after failed antireflux surgery: a systematic review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:1539-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Symons NR, Purkayastha S, Dillemans B, et al. Laparoscopic revision of failed antireflux surgery: a systematic review. Am J Surg 2011;202:336-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wee JO. Redo laparoscopic repair of benign esophageal disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:S71-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith CD, McClusky DA, Rajad MA, et al. When fundoplication fails: redo? Ann Surg 2005;241:861-9; discussion 9-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furnée EJ, Draaisma WA, Broeders IA, et al. Surgical reintervention after antireflux surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a prospective cohort study in 130 patients. Arch Surg 2008;143:267-74; discussion 74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iqbal A, Awad Z, Simkins J, et al. Repair of 104 failed anti-reflux operations. Ann Surg 2006;244:42-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khajanchee YS, O'Rourke R, Cassera MA, et al. Laparoscopic reintervention for failed antireflux surgery: subjective and objective outcomes in 176 consecutive patients. Arch Surg 2007;142:785-901; discussion 791-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sathasivam R, Bussa G, Viswanath Y, et al. 'Mesh hiatal hernioplasty' versus 'suture cruroplasty' in laparoscopic para-oesophageal hernia surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg 2019;42:53-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, et al. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 2006;244:481-90. [PubMed]

- Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG, et al. Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg 2011;213:461-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oelschlager BK, Yamamoto K, Woltman T, et al. Vagotomy during hiatal hernia repair: a benign esophageal lengthening procedure. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1155-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oelschlager BK, Lal DR, Jensen E, Cahill M, et al. Medium- and long-term outcome of laparoscopic redo fundoplication. Surg Endosc 2006;20:1817-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Del Campo SE, Mansfield SA, Suzo AJ, et al. Laparoscopic redo fundoplication improves disease-specific and global quality of life following failed laparoscopic or open fundoplication. Surg Endosc 2017;31:4649-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto SR, Hoshino M, Nandipati KC, et al. Long-term outcomes of reintervention for failed fundoplication: redo fundoplication versus Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Surg Endosc 2014;28:42-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Little AG, Ferguson MK, Skinner DB. Reoperation for failed antireflux operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;91:511-7. [PubMed]

- Madalosso CA, Gurski RR, Callegari-Jacques SM, et al. The Impact of Gastric Bypass on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Morbidly Obese Patients. Ann Surg 2016;263:110-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Awais O, Luketich JD, Tam J, et al. Roux-en-Y near esophagojejunostomy for intractable gastroesophageal reflux after antireflux surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1954-9; discussion 9-61.

- Makris KI, Panwar A, Willer BL, et al. The role of short-limb Roux-en-Y reconstruction for failed antireflux surgery: a single-center 5-year experience. Surg Endosc 2012;26:1279-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Kavanagh R, Nau P. Laparoscopic surgical treatment for recurrent gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2019;4:85.