Site of extraction for laparoscopic colectomy: review and technique

Introduction

After the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy three decades ago, laparoscopic techniques have been extensively implemented in many arenas of surgery, including colon surgery. Numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown the beneficial outcomes of laparoscopic colon surgery, which includes reduced pain, earlier recovery and shorter length of stay at the hospital (1).

After laparoscopic colon resection, an incision—also known as a minilaparotomy—is usually necessary for two major reasons: creation of the intestinal anastomosis, and specimen extraction. The size and location of the minilaparotomy have a profound impact on short and long-term recovery after laparoscopic colorectal surgery (2).

Incisional hernia (IH) has an impressive economic burden on the healthcare system, and profound physiological and psychological effects on patients (3,4). IH is a common long-term complication after open colon surgery, found in about 20% of the patients who undergo the procedure. Trocar-site and specimen extraction site both can also cause IH after laparoscopic colorectal surgery but the latter contributes more to the incidence of IH and is the most important modifiable factor to influence IH in laparoscopic colectomy (5-8).

It was proposed that the implementation of laparoscopic technique would diminish the risk of IH (9,10), however, some studies with long-term follow up have demonstrated conflicting results that laparoscopic colon surgery has similar risk of IH when compared to open colon surgery (11).

Wound infection is another dreaded postoperative complication that can result in an increased hospital length of stay, recovery time and burden of cost on healthcare system (12,13). Wound infection rates between 5% and 30% have been reported in patients who undergo colon surgery (14-18). Due to the fundamental difference between the technique of laparoscopic and open colon surgery, it was expected that the wound infection rate would be lower with a laparoscopic technique as it was in other surgical specialties (19,20). However, it has been observed that the extraction site behaves in a similar manner as a traditional midline incision in terms of wound-related complications (11).

Due to the above-mentioned concerns, there is a growing desire among surgeons to optimize the size and location of the specimen extraction incision in order to retain the maximum advantages of a minimally invasive procedure. This has led surgeons to investigate different approaches to specimen retrieval: from an incision at or away from the port sites to methods for extracting the specimen without a need for an incision altogether. Here, we discuss different approaches to specimen extraction after laparoscopic colectomy.

Periumbilical incision

In this technique, the umbilical trocar (if present) is removed for the extraction of the specimen, an endobag is inserted and the specimen is placed in it while the abdominal cavity is inflated. An incision is made along the circumference of the umbilicus around the umbilical ring. For extraction, the umbilical incision is extended 3 to 5 cm in a cranial to caudal direction at the fascia and skin and slight traction is exerted on the bag which results in the removal of the specimen without any risk of neoplastic seeding. Alternatively, the wound can be covered with a wound protector and the specimen is extracted without an endobag (21).

The advantage of this technique is its rapidity and that an entirely separate incision is not needed for the extraction of the specimen. In addition, the circumference of the cutaneous scar can be hidden by the umbilical scar. Naturally the cosmetic advantage of this approach is limited by the size of the specimen being extracted as it may not be an appropriate approach for the extraction of a specimen greater than 6 or 7 cm (8). In addition, there is a high rate of subsequent umbilical IHs (4).

Transverse incision through the right or left iliac fossa

Iliac incisions are made parallel to the inguinal ligament. The incision starts medially to the anterior superior iliac spine and terminates at the lateral border of the rectus muscle. The external oblique, internal oblique, transverse muscle and transverse fascia are dissected exposing the peritoneum which is then dissected with fingers (22).

This technique is useful for removal of a large specimen. The right iliac fossa is used for the retrieval of the specimen if right hemicolectomy is done whereas the left iliac fossa is used if the left hemicolectomy or sigmoidectomy is done. The size of the incision is dependent on the diameter of the tumor to be delivered but in most cases the size is between 4 and 8 cm (23).

A study done by Kam et al. (24) included a retrospective review of 280 randomly selected patients who underwent open colon resections for colorectal cancer. 140 procedures were done with a midline incision whereas the other 140 were performed with an incision in the left iliac fossa. They concluded that the patients with incision in left iliac fossa had earlier ambulation, less narcotic use and length of stay at the hospital.

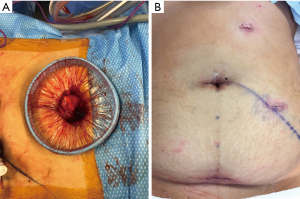

Pfannenstiel incision

It is a lower abdominal transverse incision which was described by Pfannenstiel in 1900 (Figure 1) (25). This incision preserves the anterior fibrous sheath (including the aponeurosis formed by the fibers of external oblique, internal oblique and transversus muscle). In this technique, a low transverse skin crease is used as a surface marking for the Pfannenstiel incision. One common technique is incising the subcutaneous fat and the anterior rectus sheath along the same line of the skin incision. Flaps are raised between the anterior rectus sheath and the rectus muscle inferiorly up to the pubic symphysis. The rectus muscle is then split and the peritoneum is incised (26).

This technique has been associated with a significantly lower incidence of IH 0% to 2% (27,28). In gynecological procedures, Pfannenstiel incision is used for the majority of pelvic procedures and has shown favorable outcomes including ileus, length of hospital stay and wound infections (27,29). A retrospective cohort study of 2,148 patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal resection was done by Benlice et al. (5) to assess the relationship between extraction site location and IH. They concluded that the preferential extraction site to minimize IH rate should be Pfannenstiel or incision off the midline whereas midline incisions should be avoided when possible.

DeSouza et al. (30) suggested two major mechanisms that protect against hernia formation after Pfannenstiel incision. They postulated that the incisions are at right angle between the anterior rectus sheath and the rectus muscle which offers a shutter valve-like action when intra-abdominal pressure is increased. Secondly, the tension lines on the anterior rectus fascia run parallel to the long axis of the incision which opposes the fascial ends.

The literature suggests that Pfannenstiel incisions result in a lower rate of IH when compared to other extraction sites. However, in order to use this extraction site for right colectomy an intracorporeal anastomosis is necessary (30,31). Intracorporeal anastomosis allows great flexibility in the extraction site which is not available when extracorporeal anastomosis is carried out as the specimen should be extracted in the vicinity of the anastomosis being performed (32,33). Moreover, unlike extracorporeal anastomosis, intracorporeal anastomosis enables resection of the right colon with minimal mobilization and mesenteric traction which decreases the rates of mesenteric tears, bleeding and tissue torsion. This may result in a faster recovery, reduced complications and adhesion formation (34).

Shapiro et al. (33) conducted a comparative study of two anastomotic techniques for right hemicolectomy in patients with malignancy. Out of 191 patients, 91 underwent intracorporeal anastomosis whereas 100 patients underwent extracorporeal anastomosis. In the group which had intracorporeal anastomosis, lower rates of IH (2.2% vs. 17.0%, P=0.001) were found which they attributed to the fact that vast majority of the patients undergoing intracorporeal anastomosis had specimen extraction performed through a Pfannenstiel incision.

Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE)

NOSE is a technique in which the specimen is retrieved via a visceral opening that is communicating with an outside world. The most common extractions are either transanal or transvaginal. NOSE significantly reduces the surgical trauma and post-operative pain as it eliminates the need of a separate incision for the specimen extraction. A meta-analyses published by Ma et al. (35) has shown that this technique of specimen extraction has many advantages which include shorter length of hospital stay, faster return of bowel function and lower post-operative pain scores.

A randomized clinical trial done by Wolthuis et al. (36) compared postoperative analgesic use between NOSE and conventional specimen extraction group. The NOSE group used significantly less acetaminophen, patient-controlled epidural analgesia and the pain scores also remained significantly lower after one week.

NOSE is of significance when treating patients with body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 as they are more prone to incision related complications and IH. However, a high BMI poses challenges to this procedure itself and an increase in BMI causes more visceral fat which may be associated with specimen bulk (37).

As a new technique for specimen extraction, this approach poses certain challenges which include disturbing an otherwise healthy organ, and the potential for seeding an unaffected organ during extraction of a neoplastic tissue (38).

Another technical problem faced by this technique is removal of proximal specimens, such as the right colon. A suitable technique for removal of the right colon is the transvaginal approach. Transvaginal NOSE has shown to be effective for both right and left sided resections. Our experience suggests caution when using the technique for extraction of large specimen and in women who have undergone prior hysterectomy (2).

Stoma site extraction (SSE)

This technique can be applied to patients who require either an ileostomy or a colostomy. In this procedure, the port is positioned at the future ileostomy site and the procedure can also be done through a single incision laparoscopy access system (SILS). This is done by using a stoma site as a port site as well as a site for specimen extraction, eliminating the need for another incision. The stoma site aperture is created by vertically dividing the anterior and posterior sheaths of the rectus muscle layers and splitting the muscle fibers (39).

A study conducted by Li et al. (40) analyzed the postoperative ileostomy complications in 738 patients. The patients who needed ileostomy were divided into two groups: SSE and non-stoma site extraction (NSSE) and were compared by BMI, age, comorbidities, etc. They concluded that SSE increases the incidence of stoma site complications including stoma prolapse, retraction, stenosis, strangulation, or abscess formation. Therefore, this technique should be used cautiously in patients requiring permanent ostomies or with an elevated BMI.

The increase in parastomal hernia rates in SSE might be due to the enlargement of the stoma site for extraction and resultant trauma on the fascia during the extraction process.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic Colon surgery has many beneficial outcomes such as lower pain, earlier recovery and shorter length of hospital stay but there are still limitations due to the minilaparotomy used for specimen extraction. Complications such as IH and wound infections continue to cause great morbidity after laparoscopic colectomy. These limitations can be minimized by the use of a carefully selected extraction site. For the majority of cases, the literature supports the use of the Pfannenstiel incision as an ideal extraction site after laparoscopic colectomy. NOSE technique is an enticing new technique that can be used in selected cases provided that the operators have the adequate skill set to perform advanced intracorporeal maneuvers.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank the staff of University of California Irvine, Department of Surgery for their undue support during the study design and manuscript preparation.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Michael J Stamos and Mehraneh Dorna Jafari) for the series “Laparoscopic Colon Surgery” published in Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ales.2019.08.03). The series “Laparoscopic Colon Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Pascual M, Salvans S, Pera M. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery: Current status and implementation of the latest technological innovations. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:704-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKenzie S, Baek JH, Wakabayashi M, et al. Totally laparoscopic right colectomy with transvaginal specimen extraction: the authors' initial institutional experience. Surg Endosc 2010;24:2048-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krpata DM, Schmotzer BJ, Flocke S, et al. Design and initial implementation of HerQLes: a hernia-related quality-of-life survey to assess abdominal wall function. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:635-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee L, Abou-Khalil M, Liberman S, et al. Incidence of incisional hernia in the specimen extraction site for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2017;31:5083-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benlice C, Stocchi L, Costedio MM, et al. Impact of the Specific Extraction-Site Location on the Risk of Incisional Hernia After Laparoscopic Colorectal Resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:743-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh R, Omiccioli A, Hegge S, et al. Does the extraction-site location in laparoscopic colorectal surgery have an impact on incisional hernia rates? Surg Endosc 2008;22:2596-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berthou JC, Charbonneau P. Elective laparoscopic management of sigmoid diverticulitis. Results in a series of 110 patients. Surg Endosc 1999;13:457-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tonouchi H, Ohmori Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Trocar site hernia. Arch Surg 2004;139:1248-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kössler-Ebs JB, Grummich K, Jensen K, et al. Incisional Hernia Rates After Laparoscopic or Open Abdominal Surgery-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg 2016;40:2319-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pecorelli N, Greco M, Amodeo S, et al. Small bowel obstruction and incisional hernia after laparoscopic and open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of comparative trials. Surg Endosc 2017;31:85-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winslow ER, Fleshman JW, Birnbaum EH, et al. Wound complications of laparoscopic vs open colectomy. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1420-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Lissovoy G, Fraeman K, Hutchins V, et al. Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control 2009;37:387-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, et al. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis 2003;9:196-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang R, Chen HH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection after elective resection of the colon and rectum: a single-center prospective study of 2,809 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2001;234:181-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, et al. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: results of prospective surveillance. Ann Surg 2006;244:758-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith RL, Bohl JK, McElearney ST, et al. Wound infection after elective colorectal resection. Ann Surg 2004;239:599-605; discussion 605-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedrick TL, Sawyer RG, Hennessy SA, et al. Can we define surgical site infection accurately in colorectal surgery? Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014;15:372-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ju MH, Ko CY, Hall BL, et al. A comparison of 2 surgical site infection monitoring systems. JAMA Surg 2015;150:51-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunt LM. The positive impact of laparoscopic adrenalectomy on complications of adrenal surgery. Surg Endosc 2002;16:252-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- den Hoed PT, Boelhouwer RU, Veen HF, et al. Infections and bacteriological data after laparoscopic and open gallbladder surgery. J Hosp Infect 1998;39:27-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casciola L, Codacci-Pisanelli M, Ceccarelli G, et al. A modified umbilical incision for specimen extraction after laparoscopic abdominal surgery. Surg Endosc 2008;22:784-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chevrel JP. Surgical Approaches to the Abdomen. Springer, 1998.

- Guillou PJ, Darzi A, Monson JR. Experience with laparoscopic colorectal surgery for malignant disease. Surg Oncol 1993;2:43-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kam MH, Seow-Choen F, Peng XH, et al. Minilaparotomy left iliac fossa skin crease incision vs. midline incision for left-sided colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol 2004;8:85-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Classic pages in obstetrics and gynecology. Hermann Johann Pfannenstiel. Uber die Vortheile des suprasymphysaren Fascienquerschnitts fur die gynakologischen Koliotomien, zugleich ein Beitrag zu der Indikationsstellung der Operationswege. Sammlung Klinischer Vortrage, Gynakologie (Leipzig), vol.97 pp. 1735-1756, 1900. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1974;118:427. [PubMed]

- Kisielinski K, Conze J, Murken AH, et al. The Pfannenstiel or so called "bikini cut": still effective more than 100 years after first description. Hernia 2004;8:177-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luijendijk RW, Jeekel J, Storm RK, et al. The low transverse Pfannenstiel incision and the prevalence of incisional hernia and nerve entrapment. Ann Surg 1997;225:365-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hesselink VJ, Luijendijk RW, de Wilt JH, et al. An evaluation of risk factors in incisional hernia recurrence. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1993;176:228-34. [PubMed]

- Orr JW Jr, Orr PJ, Bolen DD, et al. Radical hysterectomy: does the type of incision matter? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173:399-405; discussion 405-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeSouza A, Domajnko B, Park J, et al. Incisional hernia, midline versus low transverse incision: what is the ideal incision for specimen extraction and hand-assisted laparoscopy? Surg Endosc 2011;25:1031-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartels SA, Vlug MS, Hollmann MW, et al. Small bowel obstruction, incisional hernia and survival after laparoscopic and open colonic resection (LAFA study). Br J Surg 2014;101:1153-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cleary RK, Kassir A, Johnson CS, et al. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis for minimally invasive right colectomy: A multi-center propensity score-matched comparison of outcomes. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206277 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shapiro R, Keler U, Segev L, et al. Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis: short- and long-term benefits in comparison with extracorporeal anastomosis. Surg Endosc 2016;30:3823-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Oostendorp S, Elfrink A, Borstlap W, et al. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in right hemicolectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2017;31:64-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma B, Huang XZ, Gao P, et al. Laparoscopic resection with natural orifice specimen extraction versus conventional laparoscopy for colorectal disease: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:1479-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolthuis AM, Fieuws S, Van Den Bosch A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic colectomy with or without natural-orifice specimen extraction. Br J Surg 2015;102:630-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camhi SM, Bray GA, Bouchard C, et al. The relationship of waist circumference and BMI to visceral, subcutaneous, and total body fat: sex and race differences. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:402-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo KM, Unal E, Marks JH. Natural orifice specimen extraction in colorectal surgery: patient selection and perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2018;11:265-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fazio VW, Church JM, Wu JS. Atlas of Intestinal Stomas. New York: Springer, 2012.

- Li W, Benlice C, Stocchi L, et al. Does stoma site specimen extraction increase postoperative ileostomy complication rates? Surg Endosc 2017;31:3552-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Chaudhry H, Pigazzi A. Site of extraction for laparoscopic colectomy: review and technique. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2019;4:87.