Radiation-induced rectovaginal fistula surgical treatment: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• The mobilization of rectal stump with a stricture via laparotomy can be challenging. A transvaginal approach through a longitudinally incised posterior vaginal wall allows for safe excision of high rectovaginal fistulas as well as meticulous dissection of the anterior rectal wall.

What is known and what is new?

• It is known that radiation-induced rectovaginal fistulas associated with rectal stricture can be challenging to manage.

• A Tuttle transvaginal access with Turnbull-Cutait pull-through and Singapore flap may decrease recurrence rates.

What are the implications and what should be changed now?

• The implications of the Tuttle, Turnbull-Cutait, and Singapore approaches include a 2-week hospital stay, facilitating the delayed coloanal anastomosis, as well as a loop ileostomy reversal after the anastomosis has healed. The following changes were made in this study: (I) the descending colon, rather than the radiated bowel, should be used for reconstruction. (II) Challenging rectal dissection can be facilitated through a longitudinal incision in the posterior vaginal wall. (III) Vaginal stenosis can be prevented by vascularized bridge closure rather than by direct suturing.

Introduction

Radiation-induced rectovaginal fistula (RI-RVF) is a complex anorectal pathology that has a significant impact on the quality of life of patients (1). It is estimated to have an incidence of approximately 3–13% (1,2), which is dependent on the study population and the time elapsed from radiation therapy. The success rate of repair varies from 18% to 93% depending on the surgical technique and patient characteristics (1,3-5). However, optimal treatment for these conditions remains unclear. We present the case of a patient who developed a high RI-RVF associated with a rectal stricture, both of which were successfully repaired in two stages via Tuttle (6) transvaginal access using the Turnbull-Cutait colon pull-through and Singapore flap. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-49/rc).

Case presentation

A 58-year-old female patient presented with a complex medical history of stage 3 Hodgkin lymphoma, obesity, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and arthritis. She also gave a previous history of pelvic radiation therapy for cervical cancer, which she received 20 years prior. After the commencement of chemotherapy for her stage 3 Hodgkin lymphoma, the patient presented to the emergency room with peritonitis due to colonic perforation and underwent an emergency laparotomy, which included an anterior resection with end colostomy. During follow-up, the patient developed a RVF and rectal stricturing, 7 cm from the anal verge. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was carried out to study the fistula anatomy and assess the integrity of the anal sphincter muscles (Figure 1). Once free of lymphoma recurrence, the patient expressed an interest in exploring options to reverse the colostomy.

All procedures that were carried out in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines established by the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. This consent may be reviewed by the editorial staff of this journal upon request.

Surgical indication

Radiation-induced proximally located rectovaginal fistulas combined with a rectal stricture represent a challenging surgical pathology, that cannot be simply repaired with excision of the fistula and re-anastomosing radiated bowel. Thus, we decided to perform a colonic pull-through to re-establish intestinal continuity, with bridge repair of the posterior vaginal wall (which had been longitudinally divided to facilitate rectal dissection after excision of the fistula) with a vascularized flap.

Surgical technique

Previously, prophylactic antibiotics were administered 30 minutes prior to the procedure. Following the induction of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned in a modified Lloyd Davies lithotomy position, and a local antiseptic measurement was taken. A cystoscopy with bilateral ureteral stent placement was performed. Additionally, a flexible proctoscopy confirmed a tight rectal stricture, located seven centimeters from the anal verge.

During laparotomy, mobilization of the fibrotic rectal stump was deemed challenging owing to the fibrotic changes. At this juncture, the posterior vaginal wall was longitudinally incised and extended up to the rectovaginal fistula, which was then carefully excised (Figure 2). Utilizing a transvaginal approach facilitated the safe dissection of the anterior rectal wall from the posterior vaginal wall, enabling the performance of the proctectomy through laparotomy down to the level of the levator ani muscle.

The hepatic and splenic flexures of the transverse colon were completely mobilized. Following the takedown of the colostomy, the descending colon was tunneled through the anal canal, and secured with interrupted sutures, thereby exteriorizing 15 cm of its most distal aspect. A Brooke loop ileostomy was then fashioned.

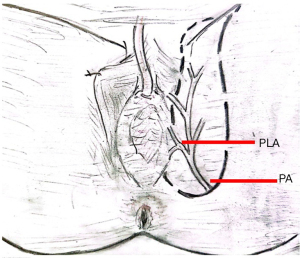

Due to concerns regarding tension and the ability to reapproximate the vaginal edges, a Singapore flap was constructed to bridge the closure of the posterior vaginal wall and to ensure adequate blood supply. This flap was sourced from the posterior labial artery, which is a subsidiary of the internal pudendal artery, and its associated profundal veins (Figure 3). The placement of the inverted U-shaped flap in the groin crease near the ischial tuberosity was accomplished after identifying its location using a handheld Doppler device. The skin and subcutaneous tissue incisions were made using an adrenaline-infiltrated incision line and a cold scalpel. The elevation of the distal portion of the flap was accomplished without the inclusion of subcutaneous tissue, resulting in a thin flap. Subsequently, electrocautery was applied to cut through the fascia and epimysium of the adductor muscles. The flap was then lifted laterally to medially and anteriorly to posteriorly. A tunnel was created beneath the left labia majora, and tissue viability was inspected using the SPY system. The graft was inserted via the tunnel from the labia majora to the vagina to complete the posterior wall vaginal repair. Interrupted polyglactin 910 sutures were applied to the edges of the graft and vaginal incision, and finally, the colon was wrapped.

On the 14th postoperative day, the patient underwent surgery, and the blood supply to the exteriorized colon was evaluated using the SPY-Elite Fluorescence imaging system®, following the administration of indocyanine green dye via intravenous injection (Figure 4). The coloanal anastomosis was securely established with the use of interrupted 3-0 silk sutures. A vaginal examination revealed satisfactory healing of the Singapore flap. After a period of 6 months, the patient reported no symptoms and demonstrated favorable functional outcomes.

Discussion

The treatment of a rectovaginal fistula depends on its location and etiology (1,4,7). RI-RVF is a challenging surgical pathology to manage. We describe a case of a high fistula associated with a rectal stricture. This case highlights the effectiveness of employing both transabdominal and transvaginal approaches in the excision of a high fistula and rectal stump resection, as well as the use of the Turnbull-Cutait colon pull-through procedure and Singapore flap for safe reconstruction, enhancing wound healing, and preventing fistula recurrence.

RI-RVF is a severe complication of pelvic malignancies (1,3,4). Patients with this condition typically have a history of having received radiotherapy several years prior, generally for the treatment of gynecological cancers. RI-RVF develops spontaneously, usually two years after radiotherapy (1,8). Multiple studies have explored the treatment options for rectovaginal fistulas of diverse origins (4,5,9). In the majority of cohort studies, the patient population with RI-RVF constituted less than 20% of the total number of analyzed individuals (1).

Management of RI-RVF should be individualized (4,7,9). The best outcomes are seen when non-irradiated tissue is involved in the reconstruction, which can be achieved with a pull-through operation and delayed coloanal anastomosis. Staged coloanal anastomosis, also known as the Turnbull-Cutait procedure, involves creating a temporary ileostomy and has been previously reported as an alternative treatment for rectovaginal fistulas (10,11). Lavryk et al. (12) recently published a retrospective series looking at the efficacy of the Turnbull-Cutait procedure in managing complex pelvic pathologies, as an alternative to permanent stoma formation, thus preserving intestinal continuity. They successfully treated rectovaginal fistulas in 85% of cases, with a recurrence rate of 8% within 6 months of surgery. According to Maggiori et al. (13), a series of cases involving rectovaginal fistulas were treated with the Turnbull-Cutait procedure as an alternative for patients at high risk of recurrent sepsis and failure with subsequent definitive stoma. The authors reported a success rate of 79% across their cohort.

The vaginal side of the fistula was repaired with tension-free, well-vascularized tissue. The Singapore flap, which was first described by We and Wee et al. (14) is a thin, highly vascularized, and pliable fasciocutaneous flap. The Singapore flap presents a highly vascularized tissue flap that is suitable for reconstruction, thereby promoting healing and minimizing the likelihood of recurrence (15).

A multidisciplinary team consisting of colorectal surgeons, plastic surgeons, and urogynecologists is crucial for effective management of rectovaginal fistulas.

The implications of the Tuttle, Turnbull-Cutait, and Singapore approaches include a 2-week hospital stay due to delayed fashioning of the coloanal anastomosis. Nevertheless, this technique could be a feasible option for repairing RI-RVFs, particularly for patients in whom preserving intestinal continuity is a viable consideration.

Conclusions

Tuttle transvaginal access, Turnbull-Cutait pull-through, and Singapore flap procedures could represent a viable reconstruction option for RI-RVFs, especially in a setting where local tissue quality is insufficient for re-anastomosis and wound healing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kelly-Ann Bobb for the English language revision.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-49/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-49/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ales-23-49/coif). R.B. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery from February 2023 to January 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures that were carried out in this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines established by the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. This consent may be reviewed by the editorial staff of this journal upon request.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zelga P, Tchórzewski M, Zelga M, et al. Radiation-induced rectovaginal fistulas in locally advanced gynaecological malignancies-new patients, old problem? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2017;402:1079-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu CY, Tseng LM, Chen HH, et al. Fatal rectovaginal fistula in post-radiotherapy locally advanced cervical cancer patients. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2022;61:1069-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nowacki MP. Ten years of experience with Parks' coloanal sleeve anastomosis for the treatment of post-irradiation rectovaginal fistula. Eur J Surg Oncol 1991;17:563-6. [PubMed]

- Gaertner WB, Burgess PL, Davids JS, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2022;65:964-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wexner SD, Ruiz DE, Genua J, et al. Gracilis muscle interposition for the treatment of rectourethral, rectovaginal, and pouch-vaginal fistulas: results in 53 patients. Ann Surg 2008;248:39-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tutlle J. A treatise on the diseases of the anus, rectum and pelvic colon. New York, NY: Appleton; 1903.

- Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Anorectal Abscess, Fistula-in-Ano, and Rectovaginal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:1117-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iwamuro M, Hasegawa K, Hanayama Y, et al. Enterovaginal and colovesical fistulas as late complications of pelvic radiotherapy. J Gen Fam Med 2018;19:166-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuma F, McKeown DG, Al-Wahab Z. Rectovaginal Fistula. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Karakayali FY, Tezcaner T, Ozcelik U, et al. The Outcomes of Ultralow Anterior Resection or an Abdominoperineal Pull-Through Resection and Coloanal Anastomosis for Radiation-Induced Recto-Vaginal Fistula Patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20:994-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsouras D, Yassin NA, Phillips RK. Clinical outcomes of colo-anal pull-through procedure for complex rectal conditions. Colorectal Dis 2014;16:253-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lavryk OA, Justiniano CF, Bandi B, et al. Turnbull-Cutait Pull-Through Procedure Is an Alternative to Permanent Ostomy in Patients With Complex Pelvic Fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2023;66:1539-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maggiori L, Blanche J, Harnoy Y, et al. Redo-surgery by transanal colonic pull-through for failed anastomosis associated with chronic pelvic sepsis or rectovaginal fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015;30:543-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wee JT, Joseph VT. A new technique of vaginal reconstruction using neurovascular pudendal-thigh flaps: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83:701-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sauseng S, Kresic J, Mayerhofer M, et al. Surgical treatment of deep-lying ano-/rectovaginal fistulas using a de-epithelialized “Singapore flap” (pudendal thigh flap). Eur Surg 2022;54:136-43. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Barzola E, Grimes C, Ritter E, Bergamaschi R. Radiation-induced rectovaginal fistula surgical treatment: a case report. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2024;9:27.